It is Saturday, the day before Remembrance Day, and I am sitting in my office, going through old letters.

These are not ordinary letters. These are dozens of first-hand accounts of life on the front lines in France during the First World War.

It is impossible to imagine what life was like for the soldiers in these muddy fields day after day, now that a century has passed.

Having said that, the ink of the handwriting on these fragile sheets of paper does feel a bit like a time machine as I run my fingers across the pages and feel the textures of the vintage paper and the ink that is raised up on the surface of these pages.

It is an eerie connection to the past and a terrible reminder of what humanity is capable of and which has been repeated many times over the last hundred years.

The voices that speak in my head as I read their words are from men who fought in France and came from countries such as Australia, England, Canada and the United States.

They are mostly young men barely out of their teens. They are still boys and they are witnessing history and surely could not realize the size of the war’s impact on the rest of the world a hundred years on.

Their words are frank and to the point as they try to illustrate their experiences to loved ones back home who are worried about them.

A Letter to Mom

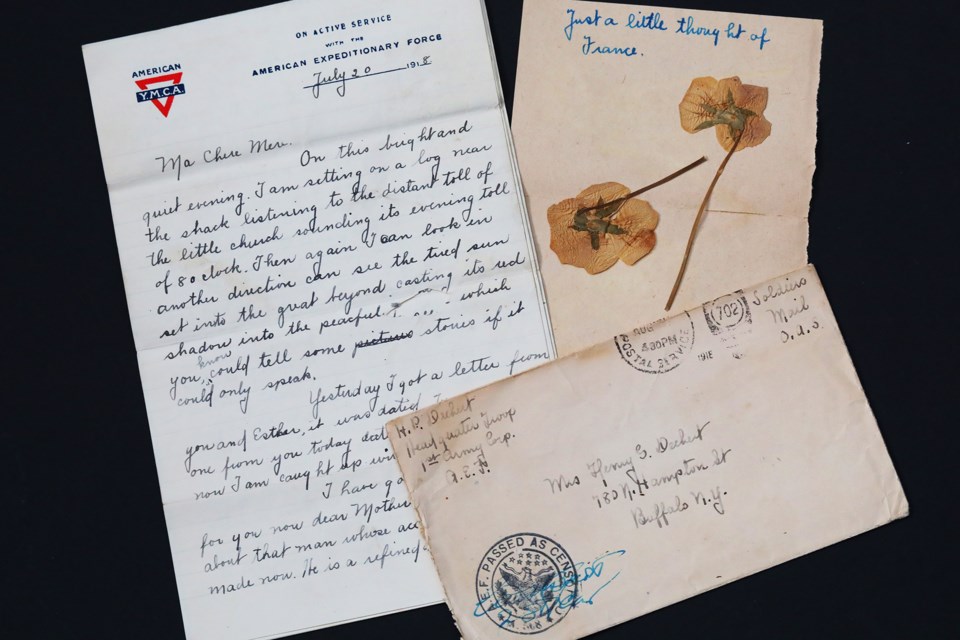

On July 20, 1918, an American soldier named Private Henry P. Dechert wrote to his mother describing the horrors of warfare as the war was grinding to a close a few months later.

“The Americans and French are sure pushing the Germans now. I fed some of them hungry Bosches the other day and said they had nothing to eat in the trenches for four days, for the Americans are picking off their supply trains and blowing them to bits.

They say the war will be over this fall. The paper here said where the Americans were battling with the Germans it was near a railroad track. Before they could run cars they had to clear the track it was three or four deep with German dead. So you can see how terrific the fighting is....Well mother dear, I am sending you two poppies. This is what the boys are adorned there in ditches when a few go when they clean up so many Bosches."

The two dried poppies that he sent to his mother are still there in the letter 100 years later.

A Doctor Captures the Moment

The most significant letter in the collection of thousands that I have amassed over the years from both world wars is one that was written by George Osborn, a major in the U.S. Army. He was a surgeon in the 40th Infantry Division. He wrote of the moments leading up to the armistice and the silence that fell over the battlefield.

In another letter dated November 7, 1918, the anticipation of peace was rapidly building. “Tonight we have news, wonderful news if true and it looks as though it might be true, the word comes over the French wire that that German generals have signed the peace agreement, which is practically an unconditional surrender....and while we have no official notice of the end of the war, it seems an assured fact, so we are all celebrating.”

Major Osborn wrote to his parents on November 14, 1918 describing the armistice on November 11 in great detail.

“The war is over as you know before this time and it will be far from news by the time you get this. I know it is over for I was there at the finish. I went up the line beyond Verdun Sunday morning and a terrific artillery duel was going on which seemed to increase rather than decrease during the afternoon.

The constant rat-a-tat of the machine guns could be heard and there were very few and very short intervals. Everyone knew that the peace - or rather the armistice might be signed at any time but it was understood that activities were not to end until 11 a.m. Monday.

The artillery kept busy most of the night and as someone expressed it - ‘who wants to sleep the last night of the big show.’ In the morning, the artillery was terrific and seemed to reach its maximum as the hour of 11 was reached. Then when the terrific uproar was at its height - it seemed to pause - there was a few scattering shots then quiet ... the most remarkable silence one could imagine. Finally one of the stretcher bearers looked up and said ‘Hell, it’s all over.’”

Radio Messages to the Troops

Two other documents that I have in relation to the armistice are the radio/wire messages at the front that were received by allied forces on the front lines.

One of them is dated November 11 at 7:50 am. It was sent by French general Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the Supreme Allied Commander. “The hostilities will be stopped on all fronts from the eleventh of November at eleven o'clock. The allied troops will not exceed until new order the line reached on this date and this time.”

It also appears that the rudimentary communications did not always reach the different regiments on the line. Another radio intercept by allied forces that was sent out by German headquarters at 4:43 pm, well after the armistice at 11 a.m., reads “Armistice signed 11-11-1155 Americans in Meuse sector please cease hostilities.”

A Letter to a Wife

One young man from Winnipeg wrote to his wife back home shortly after the war ended.

Sergeant Arthur E. Price, who served in France in the 9th Battalion, Canadian Railway Troops, spoke to her about his attempt to keep her from worrying about him during the war.

“I just keep saying to myself, well I have a chance of getting home now which was very slim when the war was on, although I did not dare to say it to you then for I knew it would worry you too much if I did so I just kept you thinking that I had a good safe job, but half the time I did not know when I would be going with a lot of the boys that used to go every day. But now I know I will be going home some day if nothing turns up unforeseen.”

The experiences varied from man to man in these letters home, but the tone is always the same: exhaustion after years of toiling on the front coupled with the anticipation of finally getting home even if they never knew when that day would finally come.

The horrors of war should never be forgotten, even if 100 years has passed. Preserving these soldiers' accounts and continuing to share them provide an important lesson of what war can bring and the lasting effects on the generations that follow.